Communion and Integral Knowledge: A Brief Introduction to the Slavophiles

Background

The Slavophiles were a group of loosely connected intellectuals in mid-19th century Russia who shared the belief that Russia's Christian past had something important to offer Europe's future. Amid rapid industrialization and cultural change, as well as Russia's growth as a major European power, Russian intellectuals in general were asking how Russia ought to conceive of itself, its past, and its future.

One group, later called 'Westernizers,' tended to think of Russia as culturally and intellectually backward, and as needing to move beyond its past and adopt Western European technology and liberal, individualistic, forms of social organization. The Slavophiles, in contrast, saw the alienation and disenchantment inherent in Western European modes of life, and, while not rejecting liberalism and technological progress tout court, saw in Russia's past something unique that Russia could contribute to the rest of the world. Above all, they were attracted to aspects of the Russian obshchina, or traditional peasant communes, and to the ecclesiology and spirituality of the Orthodox Church.

The original core group of Slavophiles included six members: Konstantin Askakov, Aleksei Khomiakov, Ivan and Peter Kireevsky, Aleksander Koshelev, and Yury Samarin. The time when these original thinkers were writing (late 1830s to 1850s) was not the most fortuitous for their particular ideas. On the one hand, the repressive regime of Nicolas I became associated with the conservative slogan of "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality." The ideas of the Slavophile movement seemed close enough to this to most intellectuals to make them immediately skeptical if not disgustedly dismissive. On the other hand, the Slavophiles were at heart Romantics and speculative thinkers who arrived at and discussed their ideas freely in a way that made them suspect to conservative intellectuals and to the state.

In spite of this intellectual isolation and lack of initial success, the Slavophile movement has turned out to be enormously influential, not only on the future of Russian political thought, but on art (especially through Dostoevsky), philosophy (especially through Soloviev), and the self-conception of much of modern Orthodoxy.

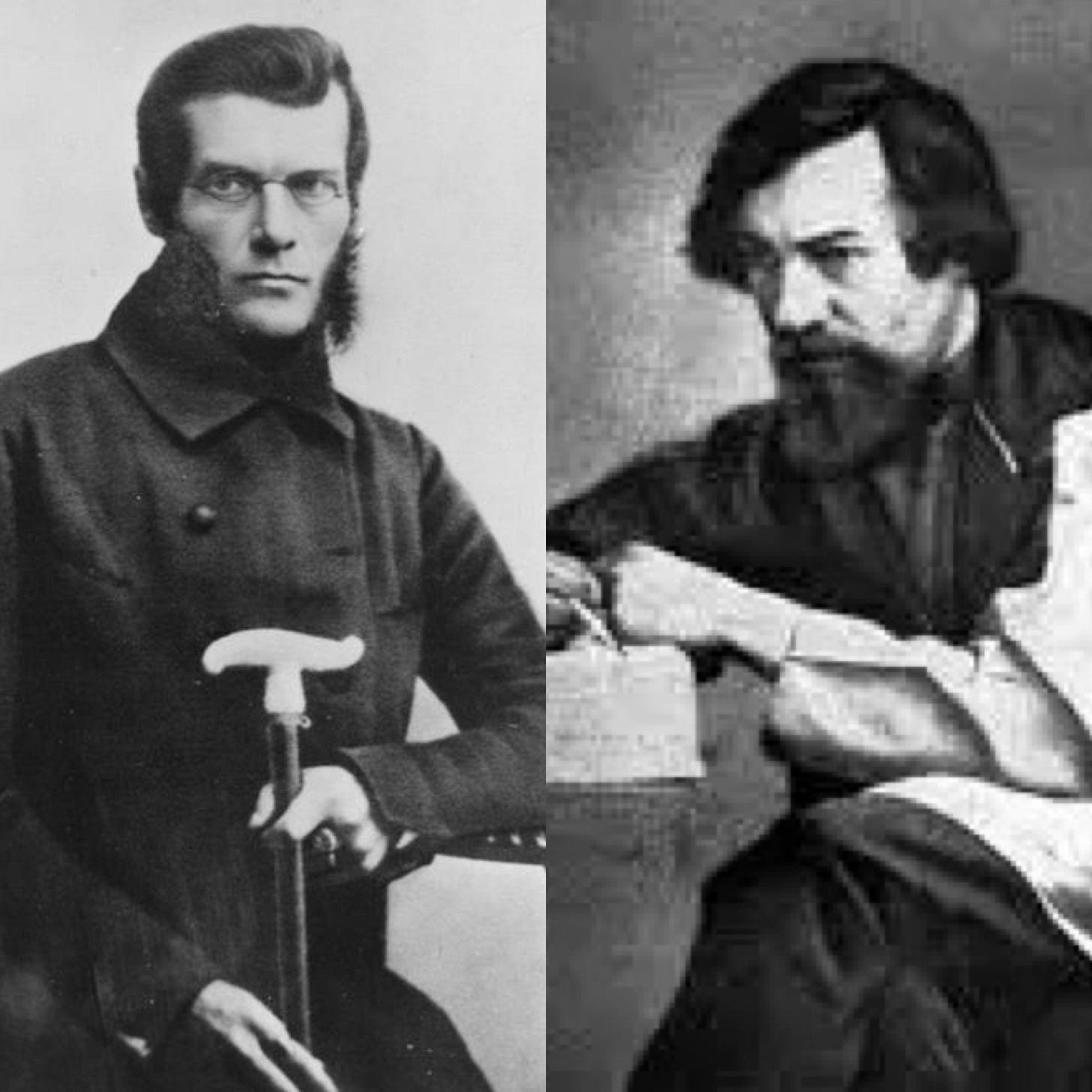

Among the early Slavophiles, the two most influential by far were Khomiakov and Kireevsky. And their two main philosophical gifts were the ideas of sobornost and integral knowledge.

Khomiakov and Sobornost

Aleksei Khomiakov was born in 1804 into a wealthy landed family. Like many of the nobility growing up at the height of Russia’s European power and cultural revival, he was very precocious. He took a primary degree in mathematics from Moscow University, but he also studied painting and knew English and French well enough to compose theological works in both languages. He dabbled in agriculture and even held a patent for a steam engine he invented for agriculture use. He composed and published poetry, and attained military honors fighting the Turks in Bulgaria. Though he published little in his lifetime, his work became enormously influential. His most famous essay, “The Church is One,” is even credited with being a major influence on Vatican II.

In seeking to understand Russia’s place in the modern world, Khomiakov turned to the religion shared with the European world, but which now divided them. In looking to what he found most appealing in traditional Russian culture, he found a sense of community based not on profit- or security-seeking, but on mutual love. As Fr. Andrew Louth puts it, “Such a society was an organic community; it was not made up of independent individuals, but was a society in which its members found their identity by belonging. It was an example of the ‘one and the many’: the one and the many balancing each other, neither reducible to the other.”

Khomiakov traced the religious roots of this feeling to the Orthodox understanding of the church as a free unity of believers. Whereas he believed that the Roman Catholics had achieved unity at the expense of freedom, and the Protestants achieved freedom at the expense of unity, only Orthodoxy preserved the ideal of a complete unity of complete freedom. This, for him, is what it means to say the Church is 'Catholic', which in the Slavonic translation of the creed is sobornyi. This ideal of free unity in love, modeled in the church, ought to be the blueprint for all human relations and communities.

Kireyevsky and Integral Knowledge

Ivan Kireyevsky, like Khomiakov, came from a family of landed nobility. Less outwardly accomplished than his fellow Slavophile, he began a career at the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Moscow, where he came into contact with Khomiakov and the "Society of Wisdom-Lovers," a group of young Russians intensely interested in Romanticism and German Idealism. Kireyevsky was initially especially captured by the philosophy of Schelling, and only gradually became attracted to the idea of the centrality of Orthodoxy for the future of Russian thought. He underwent a conversion of sorts, largely thanks to his wife Natlya Arbeneva.

First of all, she brought him into contact with a monastic elder, Fr. Philaret, which was a precursor to his later "celebrated spiritual friendship and literary collaboration" with Makary, the most famous elder of the Optina monastery. Secondly, she encouraged him to become more acquainted with the great Fathers of the Church. "It is told that when, at Kireevsky's request, his wife read works by Victor Cousin and F.W.I. Schelling, she claimed that they added nothing to what she had already learned from the Fathers of the Church. Gradually, Kireevsky began to read the Fathers, especially Isaac the Syrian and Maximus the Confessor." After this, he spearheaded efforts at making translations of these fathers available in Russian, and the ultimate goal of his philosophy became dedicated to the hope that Russia might develop a philosophical language faithful to the spiritual writings of the Greek and Slavic spiritual writers.

Like his big influence Schelling and his fellow romantics, Kireevsky was fundamentally interested in the idea of unity, in an organic and hierarchical sense: in particular, the unity of people in a society, and of the various faculties in a person. For the former, he, like Khomiakov, looked to the form of the Orthodox Church and early Russian culture. For the latter, he turned to the patristic idea of the "heart" as the deepest faculty in man, as an intuitive faculty where one knows God beyond the realm of conceptual thinking and which unifies and illuminates all the rest of one's life. Only through faith, Kireyevsky thought, is it possible unify our various faculties and to overcome the abstract rationalism that threatened to make genuine knowledge of reality as it truly is impossible.

In a revealing and oft-cited passage from the ‘Fragments’, he wrote that faith:

embraces the entire wholeness of the human being . . . Therefore, believing thought is best characterized by its attempt to gather all the separate parts of the soul into one force, to search out that inner heart of being where reason and will, feeling and conscience, the beautiful and the true, the wonderful and the desired, the just and the merciful, and all the capacity of the mind converge into one living unity, and in this way the essential human personality is restored in its primordial indivisibility.

Furthermore, this unity is achieved at the individual and social levels above all through moral understanding and action:

Each moral victory hidden in a single Christian soul is already a spiritual victory for the entire Christian world...For as in the physical world the celestial bodies gravitate to each other without any material mediation, so in the spiritual world each spiritual personality, even without visible action, by the mere fact that it abides on a moral height, lifts and attracts to itself all that is similar in human hearts. But in the physical world each being lives and is supported only by the destruction of others: in the spiritual world, the creation of each personality creates all, and each breathes the life of all.

It is in this way that sobornost and integral knowledge become connected and interdependent. Though it would take later thinkers to make this connection more clear, this connection is fundamentally ontological. The fundamental reality is spirit, and this Spirit is God. Yet, as Khomiakov once put it, the Trinity is the 'inner definition of divinity'. In other words, the most fundamental definition of reality is the communion of persons in mutual love. We can only reflect, and only come to know this reality, can only become true persons ourselves, when we achieve sobornost in our own lives. And we learn this most fundamentally in the Church and in moral action.

(Unless otherwise noted, quotations come from the introduction to On Spiritual Unity: A Slavophile Reader, ed. Jakim and Bird)

How does Dostoevsky fit into this movement?