Symbol and Substance in Politics

How the right and the left undermine themselves by ignoring material conditions

I. Jonathan Pageau recently (re-)posted to twitter an article he co-wrote with Jordan Peterson called “Identity: Individual and the State versus the Subsidiary Hierarchy of Heaven,” and it got me thinking again about some of my disagreements with the particular brand of conservatism occupied by people in that sphere. On the one hand, I agree that symbolism is an extremely important and unavoidable part of reality, as is hierarchy (though we’d probably disagree about what sorts of hierarchies ought to be endorsed or encouraged rather than dismantled). I also agree that subsidiarity ought to be a fundamental principle of moral/political thinking, and that the primary ethical duty for each person is to pursue virtue in their everyday lives and relationships. For all that, I also think the political movements supported (both implicitly and explicitly) by Peterson, Pageau, and those adjacent to them, are at best counter-productive to these ideals and at worst directly contradictory.

In short, the basic problem I think is a refusal to take seriously enough material conditions, the failure to see the ways that history and economic modes of production block from us certain possibilities for leading good lives. I was initially going just to comment on that, but (thanks to the comments of a couple friends) I came to see that a very similar charge can be raised against many on the progressive left as well, based on the work of Musa al-Gharbi and his concept of “symbolic capitalism,” the way that (mostly) elites of various types use adherence to certain symbolic aims in largely symbolic ways to reproduce the very sorts of injustices they claim to be against. In both the conservative and left versions, social commitments become largely performative, lacking any real power for transformation.

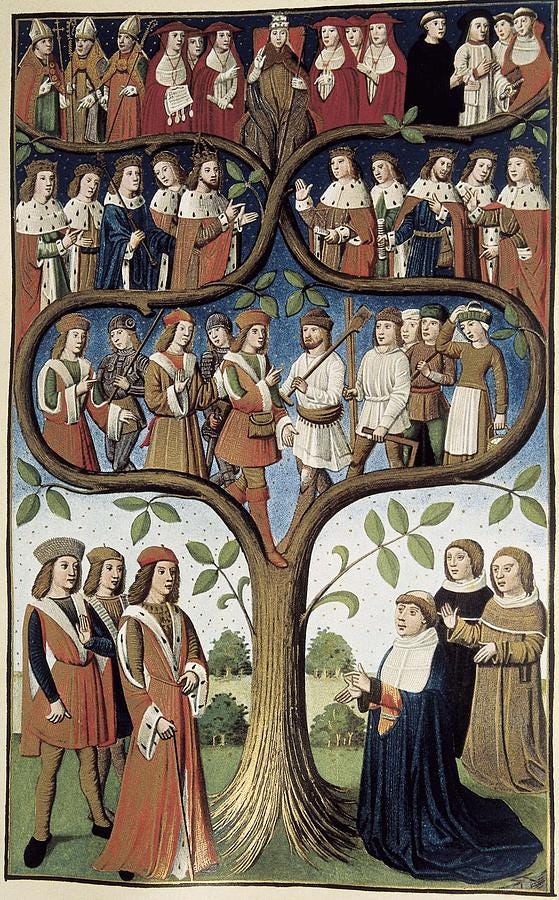

II. On the conservative side, there is all of this talk about community, tradition, and virtue. There is railing against individualism and acquisitiveness, and a call to envision life as reflecting a cosmic and social order that we are called to make real and inhabit. We ought to love truth, create lasting beauty, live in stable and loving families in stable caring communities.

So far, so good. But why have communities and families become so unstable? Why are we less concerned with truth, with beauty? The answer isn’t, as most conservatives seem to think, simply that generations have been brainwashed by professors or advertising (though the latter is closer to the truth). It’s that in a market economy, the whole social structure is set up to undermine these very things. As David Bentley Hart puts it in his essay, “Mammon Ascendant”:

The history of capitalism and the history of secularism are not two accidentally contemporaneous tales, after all; they are the same story told from different vantages. Any dominant material economy is complicit with, and in fact demands, a particular anthropology, ethics, and social vision. And a late capitalist culture, being intrinsically a consumerist economy, of necessity promotes a voluntarist understanding of individual freedom and a purely negative understanding of social and political liberty. The entire system depends not merely on supplying needs and satisfying natural longings, but on the ceaseless invention of ever newer desires, ever more choices. It is also a system inevitably corrosive of as many prohibitions of desire and inhibitions of the will as possible, and therefore of all those customs and institutions—religious, cultural, social—that tend to restrain or even forbid so many acquisitive longings and individual choices.

This is what Marx genuinely admired about capitalism: its power to dissolve all the immemorial associations of family, tradition, faith, and affinity, the irresistible dynamism of its dissolution of ancient values, its (to borrow a loathsome phrase) “gales of creative destruction.” The secular world—our world, our age—is one from which as many mediating and subsidiary powers have been purged as possible, precisely to make room for the adventures of the will. It is a reality in which all social, political, and economic associations have been reduced to a bare tension between the individual and the state, each of which secures the other against the intrusions and encroachments of other claims to authority, other demands upon desire, other narratives of the human. Secularization is simply developed capitalism in its ineluctable cultural manifestation.

As Alasdair MacIntyre puts it somewhere, the problem with conservatives is that by the time they realize what needs conserving, the revolution has already happened. There is no going back, only forward. And as he puts it in his introduction to Virtue and Politics, "As you and I encounter the resistance elicited by any systematic attempt to achieve central human goods, we learn how to define what we are politically." Doing this requires taking seriously our place in history (e.g., in the absence of some global catastrophe, a globalized and digitalized world) and the actual causes of the declines we regret. When conservatives call for a return to symbolic orders without addressing the forces that destroyed them, they are left with nothing but grievance and nostalgia.

III. On the other side of the spectrum, those who consider themselves most progressive are often equally guilty. In We Have Never Been Woke, Musa al-Gharbi describes a class (or pseudo-class) of “symbolic capitalists.” These are not usually owners of capital in the traditional sene, but those who collect and wield symbolic capital—prestige, credentials, moral and epistemic authority—like academics, journalists, managers, etc.

These figures often loudly position themselves as critics of capitalism and the inequalities and marginalization that results from it. Yet by focusing on identity and representation, educational and symbolic initiatives, etc., rather than real accountability or material redistribution, they continue to benefit from and perpetuate the system without bringing about any real (non-symbolic) changes. They give the capital owners a clean conscience without significantly helping the marginalized in any way. The left wins cultural battles in elite spaces while ceding material ground everywhere else. (My favorite meme version of this is an image which shows a business that proudly displays a sign saying that their restrooms are gender neutral, whereas visible in the periphery is another sign which also adamantly insists that restrooms are for paying customers only.)

III. Both left and right, then, are too often involved in a politics of performance. Conservatives perform tradition without doing what is necessary to build the institutions required. Progressives perform justice without changing the basic structures.

And, unfortunately, this isn’t likely to go away any time soon. One reason is that performance is easy while actual politics is hard. Another is that media rewards and amplifies such performance. Anger pleases the advertisers and wins the elections. Symbolic politics is both cheap and profitable. It is also hollow.

What we need instead is practice and real solidarity. Both tradition and justice require material conditions to thrive and survive. Families need time and security. Virtue is formed through stable institutions. Justice requires real redistribution. More than symbolic inclusion, people need shelter, stability, education, and care.

It's not a great problem to have, is it? I mean, there are lots of very, very rich people who would probably rather kill the rest of us than submit to having their immense wealth redistributed, and they've also convinced about 99% of the population that either 1) this horrible economic order is nothing but justice and freedom, or 2) that the real problem with capitalism is that there aren't enough trans billionaires. And they control the means of mass discourse (i.e. the algorithm), so those two opinions will always be dominant and always at each others' throats, and nothing more sane will ever get a hearing. Oh, and actually wading into political discourse to try and change hearts and minds is objectively terrible for your mental health in a way that can endanger your life. What to do when faced with a situation when despair seems completely rational? What do we dare hope for?

Thanks for this, Jeremiah. I agree with a lot of the particular points made, though I fear it may fall prey to the sort of explanatory reductionism/monism characteristic of modern thinking about social and political life (or really, about everything). At least, even if this wasn't your intention, I think some of what you say here might be misread that way.

I've been planning on writing a short post about the modern inclination towards explanatory reductionism/totalizing theories of social and political life, God willing I'll get to it soon. Suffice it to say for now I'm a conservative in some sense or other, and do agree that, until recently, most American conservatives have undervalued the role of material conditions in sustaining virtue and the good life. So thank you again for drawing attention to this!