The Church Fathers were not literalists

Responding to the claim that the allegorical never trumps the historical

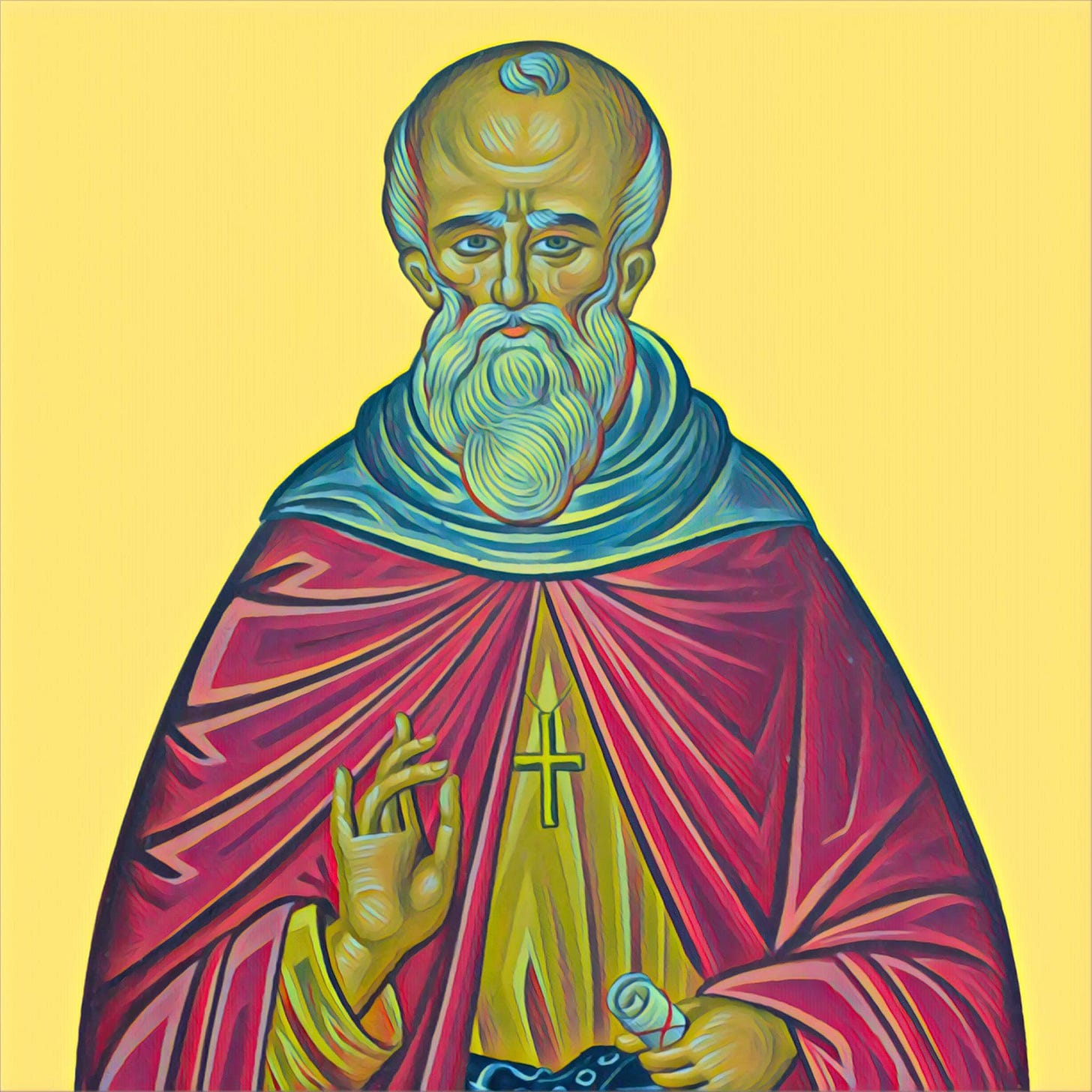

During the trial of St. Maximus for his teaching on the two wills of Christ, the bishop representing the emperor suggested that it would be better to stick to the “simple words” of Scripture without entering into elaborate speculations. The saint responded: “In saying this, you are introducing new rules for exegesis, foreign to the Church’s tradition. If one may not delve into the sayings of Scripture and the Fathers with a speculative mind, the whole Bible falls apart, Old and New Testament alike...[Those content with the simple words of Scripture] carry a covering over their hearts, so as not to see that “the Lord is Spirit” (2 Cor 3:17), hidden within the letter, and that he says, “The letter kills, it is the Spirit that gives life!”” (2 Cor 3:6).'

Elsewhere, he says that “all sacred Scripture can be divided into flesh and spirit as if it were a spiritual man. For the literal sense of Scripture is flesh and its inner meaning is soul or spirit. Clearly someone wise abandons what is corruptible and unites his whole being to what is incorruptible….Hence a person who seeks God with true devotion should not be dominated by the literal text, lest he unwittingly receives not God but things appertaining to God; that is, lest he feel a dangerous affection for the words of Scripture instead of for the Logos” (Two Hundred Texts on Theology).

When discussing passages like these, and the sorts of allegorical approaches to Scripture one finds in Origen, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Maximus, and many other Church Fathers, a certain caution is often expressed, especially when people are tempted to appeal to allegory to dismiss the historicity of troubling passages in Scripture (or, if they are taken to be historical, to dismiss the idea that they necessarily teach religious truth when understood in their historical sense). It is often said, in particular, that, though the Church Fathers may occasionally allegorize Scripture, they never do so in a way that replaces or denigrates the literal, historical understanding.*

Curious whether such a statement is really universally true, I did a bit of digging. It turns out that it is not. Here are a few representative counterexamples. And, keep in mind, I found these within a relatively short time of just searching through easily accessible online versions of texts. I'm sure that deeper digging would produce even more examples.

(Origen is quite clear on this, but I will not include him since he is viewed by many Orthodox as a heretic rather than a Church Father. Still, for example, here is a statement from his 15th homily on Joshua: "Unless those physical wars bore the figure of spiritual wars, I do not think the books of Jewish history would ever have been handed down by the apostles to the disciples of Christ, who came to teach peace, so that they could be read in the churches...”)

St. Gregory of Nyssa, to begin with, seems willing to dismiss both the historicity and the goodness of the text understood literally when failing to do so would offend common sense or morality, or contradict what is said elsewhere. For example, he dismisses the idea that the "skins" God used to cover Adam and Even could have been literal animal flesh as unreasonable: “A doctrine such as this is set before us by Moses under the disguise of an historical manner. And yet this disguise of history contains a teaching which is most plain. For after, as he tells us, the earliest of mankind were brought into contact with what was forbidden, and thereby were stripped naked of that primal blessed condition, the Lord clothed these, His first-formed creatures, with coats of skins. In my opinion we are not bound to take these skins in their literal meaning. For to what sort of slain and flayed animals did this clothing devised for these humanities belong?” (On the Soul and the Resurrection, in Schaff ed. NPNF2-05, pp. 1961-1962)

Elsewhere, he also rejects the idea that God would literally kill the firstborn of the Egyptians as punishment to Pharoah as inconsistent with God's goodness:

“It does not seem good to me to pass this interpretation by without further contemplation. How would a concept worthy of God be preserved in the description of what happened if one looked only to the history? The Egyptian acts unjustly, and in his place is punished his newborn child, who in his infancy cannot discern what is good and what is not. His life has no experience of evil, for infancy is not capable of passion. He does not know to distinguish between his right hand and his left. The infant lifts his eyes only to his mother's nipple, and tears are the sole perceptible sign of his sadness. And if he obtains anything which his nature desires, he signifies his pleasure by smiling. If such a one now pays the penalty of his father's wickedness, where is justice? Where is piety? Where is holiness? Where is Ezekiel, who cries: The man who has sinned is the man who must die and a son is not to suffer for the sins of his father? How can the history so contradict reason? Therefore, as we look for the true spiritual meaning, seeking to determine whether the events took place typologically, we should be prepared to believe that the lawgiver has taught through the things said. The teaching is this: When through virtue one comes to grips with any evil, he must completely destroy the first beginnings of evil” (Life of Moses II. 91-92).

St. Jerome says that the perfectly symmetrical measurements given to the city of Cain in Scripture are absurd and therefore must not be understood literally: “Evidently this description cannot be taken literally (in fact, it is absurd to suppose a city the length, breadth and height of which are all twelve thousand furlongs), and therefore the details of it must be mystically understood. The great city which Cain first built and called after his son must be taken to represent this world, which the devil, that accuser of his brethren, that fratricide who is doomed to perish, has built of vice cemented with crime, and filled with iniquity" (Letter to Marcella, in Schaff ed. NPNF2-06, pp.980-1).

St. Neilos the Ascetic, a writer included in the Philokalia who is said to have been a disciple of St. John Chrysostom, says that there are often details in Scripture which seem unbelievable when taken literally, which are an indication they are meant to teach a spiritual truth instead:

“The story of Ish-bosheth also teaches us not to be over-anxious about bodily things, and not to rely on the senses to protect us. He was a king who went to rest in his chamber, leaving a woman as door-keeper. When the men of Rechab came, they found her dozing off as she was winnowing wheat; so, escaping her notice, they slipped in and slew Ish-bosheth while he was asleep (cf 2 Sam. 4:5-8). Now when bodily concerns predominate, everything in man is asleep: the intellect, the soul and the senses. For the woman at the door winnowing wheat indicates the state of one whose reason is closely absorbed in physical things and trying with persistent efforts to purify them. It is clear that this story in Scripture should not be taken literally. For how could a king have a woman as doorkeeper, when he ought properly to be guarded by a troop of soldiers, and to have round him a large body of attendants? Or how could he be so poor as to use her to winnow the wheat? But improbable details are often included in a story because of the deeper truth they signify” - St Neilos the Ascetic (Ascetic Discourse, Philokalia, Vol. VI, p. 210).

There's an interesting passage in St. Maximus the Confessor's Ad Thalassium 17 which shows his exegetical commitments (he's responding to a worry about how a particular passage portrays God's dealings with Moses): "Whoever intelligently examines the enigmas of the Scriptures with a fear of God and for the sake of the divine glory alone, and removes the letter as though it were a curtain around the spirit, 'shall discover everything face to face', as the wise proverb says..." Then, later, after giving a long, highly allegorized, interpretation of the passage: "Therefore the word of Holy Scripture remains good and noble, always offering spiritual truth in place of the literal for those who lay hold of is saving meaning with the eyes of the soul. The scriptural word contains nothing slanderous of God or his holy angels. For according to the spiritual sense of this text..." While he finishes by very briefly saying there's a way even to understand the literal meaning as unobjectionable, there seems to be an implication in that last bit that we may find things which can only be interpreted slanderously 'by the letter', and so must be made sense of 'in the spirit.'

His Ambiguum 48 gives an example of a case where he thinks the literal sense of the text makes no historical sense. Rather than dismiss the text as a whole, though, he interestingly insists that Scripture sometimes contains literal contradictions for the purpose of awakening our minds to search for the deeper meanings: “Before touching on the contemplation of these matters, however, I am astonished and amazed at how Uzziah, though he was king of Judah, according to the literal account, had “vine-dressers on Mount Carmel,” which did not belong to the kingdom of Judah, but rather to the kingdom of Israel, during whose reign the city of the kingdom of Israel was built. But apparently the text has mixed into the web of the literal account something that has no existence whatsoever, thereby rousing our sluggish minds to an investigation of the truth. To begin, then, Uzziah is the intellect that has acquired divine might with respect to practice and contemplation" (Amb. 48.11-12).

As I said, these are just a few examples that I was able to find relatively quickly. But I think they prove the point well enough, and provide for a deeper and more liberating approach to Scripture than one typically sees willingly countenanced by orthodox Christians of any sort. If readers are willing to provide more citations, I'd be very interested to add them to my collection!

*It is also worth pointing out that we moderns typically use 'literal' in a way that is not always consistent with ancient usage. 'Literal' means, literally, something like 'according to the letter.' So when St. Augustine, for example, insists that we take Scripture literally, what he means is just that we must pay attention to the actual words. This is not to say that allegorical interpretations cannot replace historical, just that the allegorical interpretations themselves must not be disconnected from the text itself.

In his ‘On Christian Doctrine,’ St Augustine writes: “We must show the way to find out whether a phrase is literal or figurative. And the way is certainly as follows: whatever there is in the word of God that cannot, when taken literally, be referred either to purity of life or soundness of doctrine, you may set down as metaphorical. Purity of life has reference to the love of God and one’s neighbor; soundness of doctrine to the knowledge of God and one’s neighbor.”

Sadly, Augustine did not invoke the above hermeneutical rule to call into question the divine commands to slaughter the Canaanites; nevertheless the rule stands.

An additional quotation in this line of reasoning:

“If there were [only] one meaning for the words [of scripture], the first interpreter would find it, and all other listeners would have neither the toil of seeking nor the pleasure of finding. But every word of our Lord has its own image, and each image has its own members, and each member possesses its own species and form. Each person hears in accordance with his capacity, and it is interpreted in accordance with what has been given to him.”

~ St Ephrem of Syria, Commentary on the Diatessaron 7.22. Trans. C. McCarthy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).