What is Capitalism, Anyway?

I start with a topic that is perhaps somewhat controversial and not directly related to a current project, but which has been on my mind after noticing that around this time a few years ago I was reading Ellen Meiksins Wood’s 1999 book, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View, a book that had a big impact on my economic/political thinking at the time. Growing up as I did in an upwardly mobile evangelical Protestant home, commitment to the virtues of capitalism might as well have been a part of my faith. Defending the divinity of Christ, the inspiration of Scripture, the lives of the unborn, and the basic goodness of capitalism: if these were not all exactly on a par, they were nevertheless part of the same package.

Early in my graduate career, when I became more interested in political questions and exposed to a wider circle of viewpoints, I began to call this into question, and eventually came to believe that capitalism is both inherently unjust as a system and that it encourages and rewards vice at the individual level. But talking about this with family and friends, even (perhaps especially) educated friends was difficult.

The main problem, I came to see, was an inability to think of capitalism as anything but natural and given, and therefore to see any real alternative. “Capitalism is just when economic transactions happen within a free market,” I was told over and over again. And how can you argue with that? We have to be able to get what we need, so we need a market. And what could be a better alternative to a free market? An unfree market? Sometimes this was presented along with a historical claim to further emphasize the naturalness of capitalism, where free markets are simply an inevitable development of primitive truck and barter systems with the development of money as a helpful go-between.

But, as David Graeber and, before him, Karl Polanyi, have insisted, the dominance and inevitability of these early bartering systems is largely a myth of modern economics. And even where there have always been markets, they have not at all always been organized along capitalist lines. Capitalism as a system cannot be fully captured by abstract definitions focused merely on the ideas of a “free market” or “private property.” Capitalism is above all else a distinctive web of social relations, one for which there are alternatives. Conceiving of such alternatives is a first step to understanding deep critiques of capitalism. Knowing the history of social/economic organization helps us to do so.

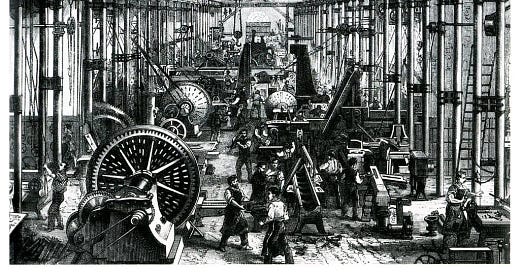

For one such alternative, for example, think of (a necessarily simplified version of) the medieval guild system. In the guild system, craftsmen of various trades belonged to organized associations with others of the same trade. These associations, the guilds, controlled the quality and quantity of the goods produced. They set standards both for the quality of the products produced and the training requirements for full standing within the guild. By limiting the number of guildsmen and products, they aimed to keep prices steady. While they of course aimed at a producing a good profit in the marketplace, this was for the profession as a whole, and there was no competition between individual members. In fact, the guild was expected to provide for its members in times of sickness, financial hardship, etc. These guilds thus served important economic and social functions.

The point here is not that we should try to recreate the medieval guild system (though I’ll admit that guild socialism holds a certain attraction to me), but to outline an alternative arrangement to capitalism. The guild system shows us a “mode of production” that is recognizably different from our own, and that allows us to see what is in fact distinctive about capitalism as a way of organizing economic life. Once we see what really came into being with the rise of capitalism, we are in a better position to evaluate the way that it orders our relations to work and to one another.

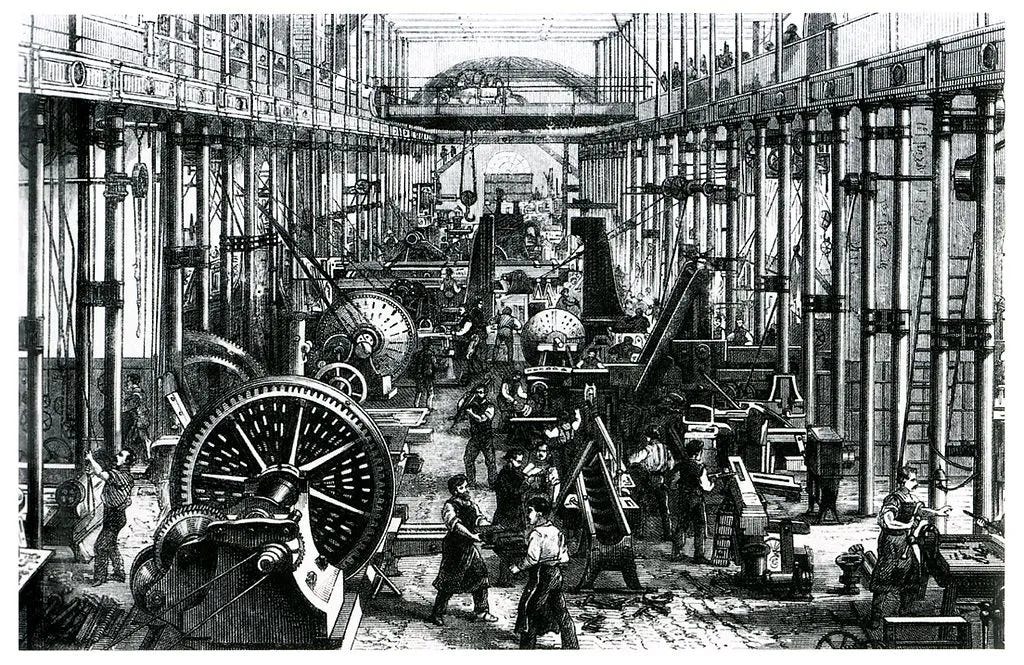

This brings me back to Ellen Meiksins Wood’s historical discussion of the origins of capitalism. She identifies three main, closely related, features that separate capitalist modes of production from all previous forms of economic organization. The persuasiveness of her claims can be seen in part by noting how well they characterize capitalist economic life, and by comparing them to the different form of economic life represented by the guild system. The three features are: (1) the stark difference between capitalists and workers, i.e., those whose livelihood is supplied by what they own, and those whose livelihood depends on selling their labor to others, (2) the new omnipresence of the market in economic life, where virtually everything one needs to live must be purchased in the market, and where even owners and laborers can only continue to exist as such by participation in the market, and (3) the fact that the necessary pressures placed by the previous two features leads to the domination in economic life of certain incentives; in particular, towards the competition of all against all, towards profit maximization, and towards the constant need to reinvest capital and grow.

Here is her own summary of these features, which I share at length for its clarity:

Here, then, is the basic difference between all pre-capitalist societies and capitalism. It has nothing to do with whether production is urban or rural and everything to do with the particular property relations between producers and appropriators, whether in industry or agriculture. Only in capitalism is the dominant mode of appropriation based on the complete dispossession of direct producers, who (unlike chattel slaves) are legally free and whose surplus labour is appropriated by purely ‘economic’ means. Because direct producers in a fully developed capitalism are propertyless, and because their only access to the means of production, to the requirements of their own reproduction, even to the means of their own labour, is the sale of their labour-power in exchange for a wage, capitalists can appropriate the workers’ surplus labour without direct coercion.

This unique relation between producers and appropriators is, of course, mediated by the ‘market’. Markets of various kinds have existed throughout recorded history and no doubt before, as people have exchanged and sold their surpluses in many different ways and for many different purposes. But the market in capitalism has a distinctive, unprecedented function. Virtually everything in capitalist society is a commodity produced for the market. And even more fundamentally, both capital and labour are utterly dependent on the market for the most basic conditions of their own reproduction...

This unique system of market dependence has specific systemic requirements and compulsions shared by no other mode of production: the imperatives of competition, accumulation, and profit-maximization, and hence a constant systemic need to develop the productive forces. These imperatives, in turn, mean that capitalism can and must constantly expand in ways and degrees unlike any other social form. It can and must constantly accumulate, constantly search out new markets, constantly impose its imperatives on new territories and new spheres of life, on all human beings and the natural environment.

If one finds this understanding of the nature of capitalism persuasive—and I do, though I think there are things to be added, especially about the rise of finance capitalism, where inordinately large sums of money are made more or less by playing games with large sums of money—then one can, perhaps, begin to understand some of the many criticism of capitalism as a form of economic organization. Certain ethical concerns seem to me fairly close at hand. I’ll leave their discussion for another time. The first thing is to understand the nature of the beast.

Hello there. I'll push back a bit. As I've said before (on a different platform in response to you), we have much in common in our love for the Russian Sophiologists, Hart, and their patristic influences (the Cappadocians, and Maximus, mainly). However, while I've done away with a literal Adam and Eve, an eternal hell, and I accept all of Bulgakov's Sophiological proposals, my belief in the free market has only grown more robust. I know Bulgakov and Hart and...pretty much all the theologians I most admire would disagree with me, but what are you gonna do? I do wonder if your family REALLY embraced markets though since I know that my folks who once sung the praises of the "free market" have no problem advocating for populist and nationalist Trumpian policies of trade restrictions, turn a blind eye to Republican support for oil subsidies that are contributing to climate change, and basically advocate for a closed border policy when it comes to immigration. Those are the furthest you can get from a free market.

The main problem I see with the definition you share of capitalism is that it essentially sounds Neo-Darwinian. Hayek, as much as he rightly advocated for thinking of market processes as being evolutionary, saw this evolutionary process as more about cooperation than cut throat competition, which now coincides with the extended evolutionary synthesis advocated by folks like Denis Noble and others.

As Mises says,

"the fundamental facts that brought about cooperation, society, and civilization and transformed the animal man into a human being are the facts that work, performed under the division of labor, is more productive than isolated work and that man's reason is capable of recognizing this truth. But for these facts men would have forever remained deadly foes of one another, irreconcilable rivals in their endeavors to secure a portion of the scarce supply of means of sustenance provided by nature. Each man would have been forced to view all other men as his enemies; his craving for the satisfaction of his own appetites would have brought him into an implacable conflict with all his neighbors. No sympathy could possibly develop under such a state of affairs."

An almost magical illustration of this, is of course the pencil, which you could never make, nor could I. I couldn't list all the jobs and states and countries involved in making one single pencil if I tried. Most of us have probably heard about the guy who tried to make his own toaster. Same thing. Didn't go too well. Something as simple as a toaster is an awe-inspiring testament to global market processes. https://www.ted.com/talks/thomas_thwaites_how_i_built_a_toaster_from_scratch/transcript?language=en

The problem with the guild system was not that they created a kind of fraternal society, but that they seemed to serve as a type of rent seeking where the states of that time could work out special deals with the guilds in order to extract the most tax revenue. They ended up keeping people out and restricting the ability of anyone not approved to be in the guild to make a living. Perhaps in an anarchist society, your guild system would work better, but I'm not sure what your ideal guild system would look like, so I'd need to know more.

Whatever the case may be, the guild system certainly did not alleviate the absolute grinding poverty that most of the world found itself in before what Deirdre McCloskey refers to as the great enrichment. As she points out over and again, "From 1800 to the present the average person on the planet has been enriched in real terms by a factor of 10, or some 900 percent." I think it's pretty difficult to argue this didn't occur because of the success of liberalism. https://reason.com/podcast/2017/08/09/deirdre-mccloskey-bourgeois-equality/

Free markets do obviously have competition as well, but so does gym class, and receiving scholarships that don't go to everyone, and getting published in scholarly journals while others are not, and getting book deals while others don't. If you were completely honest, would you write this blog post on capitalism if you were 100 percent sure that no one would ever read it? If you hope for readership, you are thereby also competing against millions of other bloggers and you are trying to show why I should spend 15 minutes reading your blog than the other person's. At the same time, however, you are part of what I hope is a growing movement of Orthodox thinkers slightly more daring and intellectually rigorous than what is usually found on popular Orthodox websites, and I hope we can all cooperate together to keep Orthodoxy from getting taken over by the young earth creationist fundamentalist nationalists.

As Denis Noble and other advocates of the extended evolutionary synthesis are now pointing out, evolution is just as much if not more so about cooperation and even, dare I say, Neo-Lamarckian mechanisms than was originally thought, and so is the free market. The Chicago school of economics had unfortunately tied the mechanistic view of evolution to economics, but that is starting to get overturned with the advent of the "humanomics" of Vernon Smith and Deirdre McCloskey. They're bringing the humanities back into economics. I'd be interested in your critique of their more "human" centered free market economics, which has shaken off the shackles of the mechanistic worldview that you are tying to markets in this blog post.

I'd love to know where you think I'm wrong or got off track.

Looking forward to continuing to read your posts. And P.S., what academic environment are you working in that free market economics is a thing? I feel like a total anomaly in the theology department I teach in. Most people seem far more on your side than mine, and this seems to be the case in most academic departments everywhere other than at decidedly conservative universities.

Peace,

"Max"