Why God Couldn't Have Created Us Already Perfect

On the perils of being a rational created being

The question is sometimes asked, "Why couldn't have God just created us perfect right from the beginning?" Usually this is in relation to the problem of evil, and, in particular, in response to a sort of free will defense which claims that it was important or necessary that God gave us free will, so that we could freely choose to do what is right and pursue a right relationship with Him, but which also leaves open the possibility of wrong choice and movement away from God. Since we know that the perfected still have free will, but always choose the good, the question arises why God couldn't have just created us in that state right away.

This question is also sometimes raised in the context of debates about universalism. Fr. James Dominic Rooney (O.P.), for example, has raised this worry multiple times on social media. The basic worry is this: The need for free choice and development of character makes sense if this is something that can go well or badly on the basis of our choice, leading ultimately to Heaven or Hell. But if everyone is going to make it to heaven eventually, what's the point? God may as well have just created all of us as already perfected from the beginning.

The best response to this worry is that the idea of creating an already-perfected creature capable of choice and self-movement is just not metaphysically possible. My first exposure to this idea came from David Bentley Hart, who expresses it like this:

>...the issue of evil isn't a utilitarian calculus, it's a matter of the process whereby nothingness and every possibility of evil inherent in the conditions of finite freedom is conquered while actually bringing free spiritual natures into existence. But spirit can exist only under the conditions of those rational conditions that logically define it. To ask why God did not create spiritual beings already wholly divinized without any prior history in the ambiguities of sin—or of sin's possibility—is to pose a question no more interesting or solvent than one of those village atheist's dilemmas: can God create a square circle, or a rock he is unable to lift? A finite created spirit must have the structure of, precisely, the finite, the created, and spirit. It must have an actual absolute past in nonbeing and an absolute future in the divine infinity, and the continuous successive ordering of its existence out of the former and into the latter is what it is to be a spiritual creature. Every spiritual creature as spirit is a pure act of rational and free intentionality away from the utter poverty of nonbeing and toward infinite union with God. This 'temporal' or 'diastematic' structure is no less intrinsic to it than is its dynamic synthesis of essence and existence, or of stability and change.[^1]

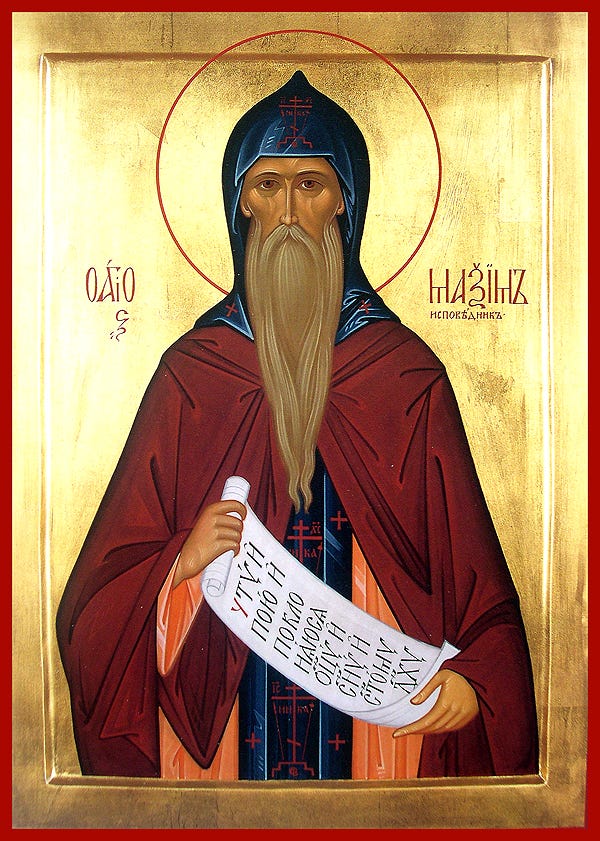

He only briefly cites St. Gregory of Nyssa as an authority behind this approach to the question, though I'm sure there are many other ancient sources that could be cited. But I've just finished one of my periodic re-readings of St. Maximus's 7th Ambiguum (which is probably the single deepest relatively short text on philosophical theology in history), and I noticed that this idea is fundamental to St. Maximus's argument in the beginning section.

St. Maximus argues that for a created being subject to movement, there are three distinct stages which are metaphysically necessary. First, there is creation/becoming/bringing into being. "...of the things made by God, coming into being precedes movement" (1072A). However, since St. Maximus, like Aristotle, believes that final causality is an essential aspect of our understanding of things, he also thinks that to be a created thing means to be directed towards some end. The second stage is movement: "The movement that is tending towards its proper end is called a natural power, or passion, or movement passing from one thing to another and having impassibility as its end. It is also called an irrepressible activity that has as its end perfect fulfillment" (1072B). Finally, there is perfection/rest/stability, which is the reaching, so far as possible, off the inherent *telos* of the thing. "It cannot be squared with the truth to propose that becoming is [immediately] prior to stability, since stability is of its nature without motion; but it is equally impossible to posit stability as the consequence of a motionless becoming, or to equate stability and becoming. For stability is not a potential condition of becoming....but is rather the end-stage of the realization of potency in the development of created things. To put it briefly, stability is a relative concept, which is not related to becoming but to movement, of which it is the contradictory" (Amb. 15).

In responding to our question, it is the second stage that is most important, that of movement. St. Maximus argues that "everything that comes into existence is subject to movement, since it is not self-moved." In other words, since the telos of something is set by its being (what it is), and since the very movement from non-being to being/becoming necessarily comes from outside of any created thing, so its end must be outside of itself as well, implying the need for movement. In rational creatures, this movement itself is essentially rational, i.e. subject to volition: "If then rational beings come into being, surely they are also moved, since they move from a natural beginning in 'being' toward a voluntary end in 'well-being'" (1073C).

If we believe in God, then we believe that both our beginning and our end are in God. God brings us into being from nothingness by giving us our being from Himself, and our purpose or reason for existence is to attain to union with Him. But since we are also rational creatures, essentially capable of reaching this Good by our own voluntary choices in accordance with perception and desire, we could not be what we are without passing through a stage of pursuit and development, moving, as St. Maximus puts it, from being, to well-being, to eternal well-being. And that is why we could not have been created already perfected: a created rational being just is a being destined to move from being to well-being to eternal well-being in virtue of voluntary choice.

[1] https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2021/08/11/dbh-on-created-spirits-and-the-possibility-of-evil/

Jeremiah Carey poses a response to an objection which I have raised against universalism. That objection, in short, is that if universalists are right that God can manipulate free choices such as to ensure that we all end up in heaven, then God can also ensure we never sin.

The best way to understand my objection to universalism is as a dilemma, hinging on the fact that most universalists are compatibilists. If the ability to sin is essential to human free choice, then one can sin at every time, such that not even God can prevent sin from occurring, which precludes God's ability to ensure universal salvation; if the ability to sin is not essential to human free choice, then God can ensure that no sin ever occur, and God can ensure universal salvation, but then ought also to ensure (by their same principles of divine love which universalists endorse) that no sin ever occur.

Carey responds by appealing to a strategy proposed by David Bentley Hart, who argues that there is a logical contradiction involved in creating a free being that is perfect from the first moment. Carey then adds references to Maximus the Confessor, who Carey interprets as posing that it is essential to rational creatures that they need to make their own choices and that not even God could create a free being perfect from the first moment of their existence. Carey refers to the following passage as evidence: "If then rational beings come into being, surely they are also moved, since they move from a natural beginning in 'being' toward a voluntary end in 'well-being'" (1073C). Thus, Carey summarizes, "since we are also rational creatures, essentially capable of reaching this Good by our own voluntary choices in accordance with perception and desire, we could not be what we are without passing through a stage of pursuit and development...."

However, neither Maximus' passage nor Hart's argument nor Carey's short inference prove what is necessary to avoid my objection. I did not assume that, if God could manipulate choices to ensure universal salvation, He could thereby create finite creatures 'perfect' without their choice or at the first logical moment of their existence, but rather that, if God could manipulate choices to ensure universal salvation, then God could also prevent all sin from occurring.

Carey's citation of Maximus is then not to the point. In the passage cited, Maximus seems to be saying that it is required of free creatures that they engage in free choice in order to attain their ends, such as voluntarily chosen happiness. But Maximus does not say here anything about [1] whether the will can be determined to a specific outcome by means of God's Providence (or whether God can indirectly ensure a given outcome) or [2] whether this situation makes it such that not even God could prevent a person from sinning without violating their free will. Maximus therefore does not here speak to whether God could prevent all sin from occurring, and so the passage is irrelevant to my dilemma.

As to [1], a compatibilist too could hold that every free creature needs to move through a period of voluntary choices. They simply think God's determining the choices to a particular outcome or indirectly ensuring that a given choice occurs is not in contradiction with the choices being voluntary. That is: you don't need to say God creates us perfect from the first moment in order to affirm that God could ensure we end up perfect and never commit a sin along the way. As to [2], there is nothing in the position that every person must make some choices to achieve their natural teleological end which precludes that God could prevent sin occurring in those choices. We don't even need to believe God determines our will to particular choices to think God can prevent sin. We might imagine that God could indirectly ensure that free creatures only had 'good options' open to them, without making them impeccable.

Hart, for instance, acknowledges that free will does not require sinning at all - and not even the ability to sin - and thus concedes the critical point that these responses do not actually avoid the objection, even if we were to grant all these claims about what is essential to free choice. In the end, then, even if it were essential to free creatures that they make voluntary choices over time, it does not follow that those choices could not be entirely determined by God's Providence or indirectly prevented from being sinful.

One possible response would involve an argument to the effect that it is essential to free will that one sin or be able to sin. But there is a problem in Christian theology if we hold that it is essential to free will that either one sin or be able to sin. On the one hand, Jesus Christ is free but impeccable. On the other hand, it is Orthodox and Catholic belief that the Blessed Virgin Mary was prevented by God's grace from ever committing a sin. And Maximus the Confessor himself plausibly - e.g., according to Christiaan Kappes - held and defended the doctrine that the Blessed Virgin was 'immaculate,' that is, preserved from original and actual sin. If it were strictly impossible for God to prevent a person from sinning, then these doctrines about the Blessed Virgin would entail a contradiction. And, if you thought that a period of sinfulness was essential to being a finite free creature, then the Fall of Adam would seem necessary - but, whereas some universalists seem to endorse such conclusions, this view that sin is necessary for our welfare is pretty bad.

Now, it is very unlikely that Maximus is either a compatibilist about freedom or a universalist. Rather, Maximus seemingly rejects universalism (when he does) on grounds of freedom, as when he talks about individuals freely or voluntarily bringing about their own eternal ill-being (rather than well-being) through their own choices. Maximus' commitments then seem to play into my dilemma for universalists. If God cannot manipulate choices to ensure universal salvation either directly or indirectly, then not even God could ensure universal salvation. If God could manipulate choices to ensure universal salvation, then God could entirely prevent sin - and He ought to, by universalist principles regarding God's 'perfect divine love.'

If Maximus the Confessor were a universalist, however, I don't see anything in what Carey cites from Maximus that provides any response to the dilemma. Maximus simply says that free creatures necessarily achieve their well-being by voluntary choices, over time. He does not give an argument that God cannot prevent those choices from being sinful. If Maximus DID pose such an argument, it would aid in undermining universalism, not supporting it, since we could then infer that not even God could prevent someone from continuing in sin forever - and hence ending up damned.

What do you make of St. Maximus’s “eternal ill-being” in contrast to “eternal well being”? Eternal ill being occurs when tropos and logos do not align.