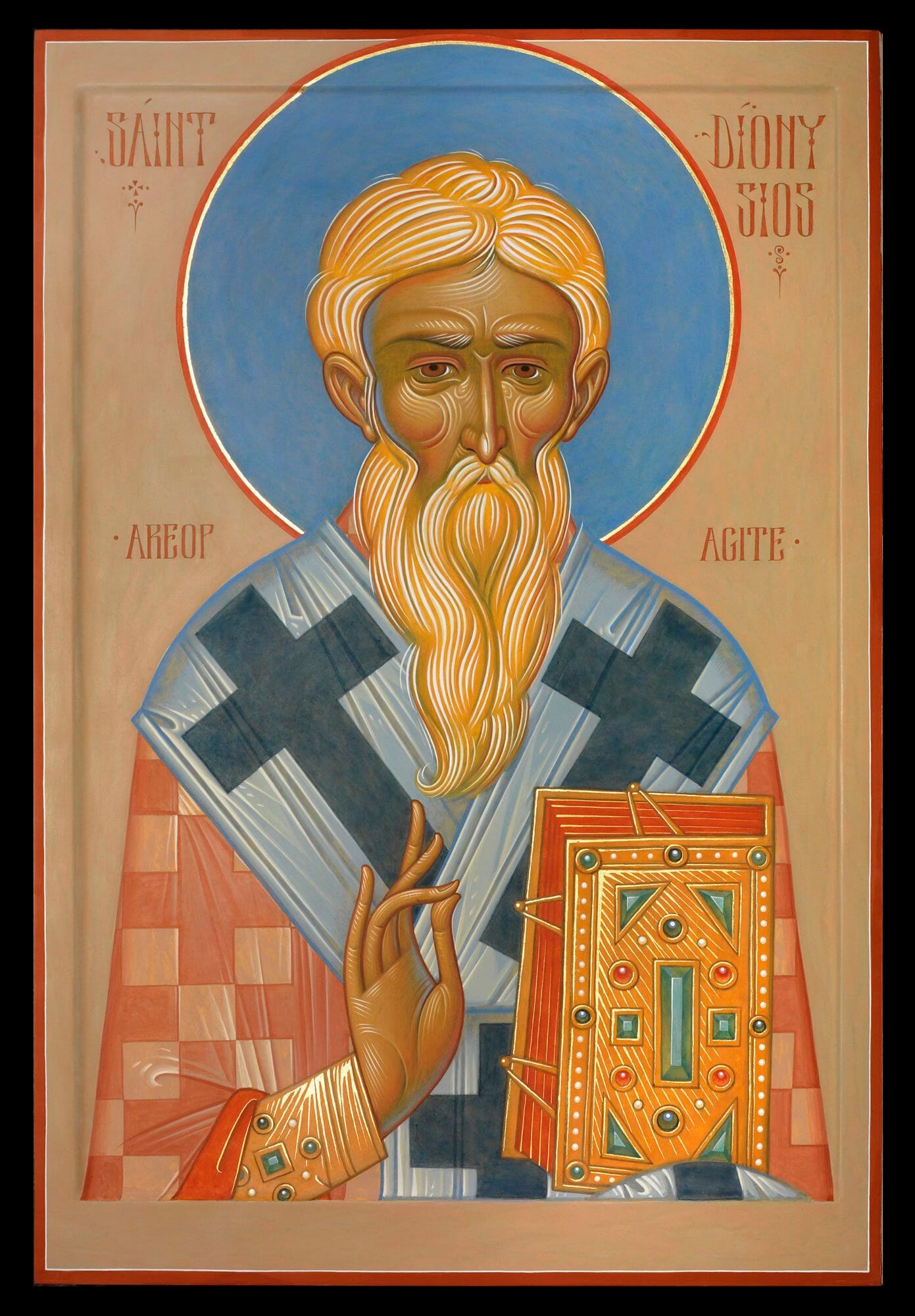

In a previous post I commented briefly on reading the works of St. Dionysius the Areopagite and finding therein what seems to me the foundational logic of the resurgence of orthodox universalism. In particular, we have the Neo-Platonic idea of abiding, procession, and return; the idea that all things pre-exist in, proceed from, participate in, and are destined to return to, God. We have the idea that all things by nature and inescapably desire Goodness and Beauty (i.e., God), and that God is (therefore) the goal/final cause of all things. And we have the idea that God, as the purely good cause of all is also the power which preserves and protects all things, and which is “to those who fall away…the voice calling, 'Come back!' and…is the power which raises them up again.”

Just this morning, I came across another passage that I could not help seeing as at least implicitly universalist, discussing ‘Salvation’ and ‘Redemption’ as names for God:

"This divine Righteousness is also praised as the 'Salvation of the World,' since it ensures that each being is preserved and maintained in its proper being and order...benevolently operating for the preservation of the world, [it] redeems everything in accordance with the capacity of things to be saved and it works so that everything may keep within its appropriate virtue. This is why the theologians name it 'Redemption,' because it does not permit the truly real to fall to nothingness and because it redeems from the passions, from impotence and deficiency anything which has gone astray toward error or disorder or has suffered a failure to reach its proper virtues. Redemption is like a loving father making up for what is missing and overlooking any slack. It raises a thing up from an evil condition and sets it firmly where it ought to be, adding on lost virtue, bringing back order and arrangement where there was disorder and derangement, making it perfect and liberating it from defects" (DN 8.9).

Two things in particular stand out to me about this text: (1) The idea of Righteousness is not connected with punishment or vengeance, but with benevolence and working to preserve the world and bring it to virtue (thanks to my friend Jesse Hake for making this clear), and (2) the insistence that everything is redeemed and kept within its proper virtue, and that nothing truly real can fall into nothingness. Again, it’s simply not clear to me how seriously we can take these commitments if there are those (perhaps a majority?) who never reach their true end and are punished and at the very least tending infinitely towards nothingness.

In response to my posting of the above quote, someone asked whether St. Dionysius was a universalist. As a not-entirely-fully-committed universalist, it seems to me that most Christian writers through the ages have probably not been universalists. It seems to me that others, such as St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Isaac the Syrian, were clearly universalists, and that any attempt to deny this is most likely a self-deceptive coping mechanism. Others, such as St. Dionysius and St. Maximus the Confessor, seem to me, like the Scriptures themselves, somewhat unclear on the matter. There are statements that seem to imply differing things. And, as mentioned in my last post, how one interprets them will to a large degree depend on how one privileges either fidelity to the letter of majority dogmatic teaching so far, or an underlying acceptance of the deep logic of the philosophical theology.

So clear and helpful.

Decades ago I did a deep dive into "righteousness" (diakiosune, GR.) and concluded it did not have to do with "justice" and retribution and balancing the scales of evil with more evil, but the bringing of things together and a "making of all things right" through love.